There are several hymns sung to the tune of the “Irish folk melody” Slane. It’s a storied tune, supposedly named after the Irish Hill of Slane were St. Patrick “lit an Easter fire in defiance of the pagan king Lóegaire”. It’s also very evocative. I first heard the tune in Lord of All Hopefulness, which ends each line with a countdown of the passing day: the break of the day, the noon of the day, the eve of the day, and the end of the day.

But my favorite is Be Thou My Vision, using words translated from a much earlier Irish poem. The original is, by tradition, attributed to the Irish poet and saint Dallán Forgaill. According to online sources, Mary Elizabeth Byrne translated “Rop Tú Mo Baile” from a Middle Gaelic poem to an English-language poem, and published it in 1905. Eleanor Hull “versified” the poem in 1912, though I can’t see whether she was versifying Byrne’s translations or going back to the original Gaelic.1

It’s not just that this earlier date puts it into the public domain that makes it my favorite—although that helps! As much as I enjoy Lord of All Hopefulness, there’s something contrived about its lyrics. In contrast, Be Thou My Vision is heartfelt and simple.

Looking at the various versions, the conversion from poem to hymn is an interesting class in how to translate a very personal prayer into a hymn to be sung during Catholic Mass.

| St. Michael Hymnal | Mary Elizabeth Byrne (1905) |

|---|---|

|

|

Compare them closely and you’ll see a degenderization in the St. Michael Hymnal version’s third verse, compared to the 1919 Church Hymnal version of Byrne’s translation. The third line of the second verse reads, in the original:

- Thou my great Father, and I Thy dear son,

- Thou in me dwelling, and I with Thee one.

Whereas in the St. Michael version, you can see it as:

- Thou my great Father, thine own may I be:

- Thou in me dwelling, and I one with thee.

Note to the bowdlerizers of great hymns: it is possible to change lyrics to actually be more universal, instead of changing them to bowdlerize God the Father and segregate humanity. The original was a personal prayer, written by an individual who, presumably—while the Irish authorship is generally attributed to Dallán Forgaill, it is by no means certain—was male. But a hymn is not normally sung by an individual, it is sung by a congregation. Mary Byrne’s original translation appears to be a translation of Forgaill’s prayer, not a conversion of the prayer into a hymn. That’s almost certainly why it was modified further to make it a Catholic hymn.

The hymn converts it from a prayer by an individual into a prayer by a congregation. Sadly, I can’t find anywhere who did that translation. Theological concerns aside, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if that anonymous Catholic wanted to convert the “I with Thee one” into “I one with thee” as much as they wanted to open the hymn to the female half of the congregation. I don’t know about UK English, but the original is very clunky in American English.

I’d also add that saying that you personally are God’s son might not be entirely appropriate despite it being true for half the population. It would certainly be more than a bit odd for all of God’s daughters. There are, however, several wonderful renditions on YouTube with the original lyrics—including by female singers. So while I agree that the changes found in the St. Michael Hymnal version are a good idea, I find it hard to fault the Petersens for disagreeing with me on this issue, or any of the other wonderful singers I’ve included in the links below.

My view comes from a Catholic layman’s perspective, of course, not Church of Ireland or Church of England. Further, there is Biblical precedent for a universal sonship.

Far more interesting are two other changes, one thematic and one metric, in the third verse (the fifth stanza of the original). In the original, the first line of the final stanza is “High King of heav’n, when the battle is done…”. “High King of heaven” is almost certainly a play on High King of Ireland, but it fits perfectly into Catholic theology so it stays. But the line is not unaltered:

High King of heaven, when vict’ry is won,

Changing this from “when the battle is done” is both a metrical change and a change in meaning. The original’s play on the high kings of Ireland was likely also a play on the many battles among Ireland’s kings, win or lose. As a hymn, the High King of Heaven will have his victory. He is not one king among many. He is the One King.

The anonymous translator also appears to have tried to maintain the meter of that line. “When the battle is done” has an extra syllable in it compared to the previous two (four in the original) verses. The change from battle to victory returns the line to the “correct” number of syllables, by glossing over victory’s middle syllable.

I notice that even those who choose to sing about being God’s son use the “vict’ry” line.

There is an opposite change in the third line of that verse. The first half of that line always has five syllables in the original. But it also always has one word for those last two notes. Always, that is, until the fifth verse, where those two notes are broken into two words, “own heart”. The word “own” is a nonce word often used by poets to maintain meter. There’s no difference in meaning between “my heart” and “my own heart”. Poetry doesn’t have a literal melody, it gets such melody as it has from its meter, which is why poets love nonce words. This isn’t necessary in a hymn.

So, “heart of my own heart” gets simplified into “heart of my heart”, and as an added benefit “heart” becomes one word, more emphasized by its spread into two notes.

Whatever lyrics you use, and whatever song you prefer to sing to the melody, you can play the melody using the piano script from 42 Astounding Scripts on the note files I’ve provided. Here’s the command I use to generate music from those files on the command line:

- ~/bin/piano [ bass.txt ] treble.txt amen.txt

Each of those text files is in the download (Zip file, 2.5 MB), but here’s amen.txt as an example:

- # Slane, Amen

- # Traditional Irish melody

- # Used for the hymns Be Thou My Vision and Lord of All Hopefulness

- # From Irish Hymnal and Tunes, p. 480-481

- prestissimo

- --key F+

- 1

- # base clef

- [-- "B. D." "F. C."]

- # treble clef

- "-B. F." "-A. F."

It’s a nice little stinger, easily recognizable as one of the many ways of singing Amen to end a hymn. If you’re not familiar with the way the piano script works, the lines beginning with a pound symbol are ignored by the script. The lines “prestissimo” and “--key F+” tell the script how fast to play and what key to play in—it will automatically add in the appropriate sharps and flats of that key. In this case, it’s the key of F Major, which has one flat, the B.

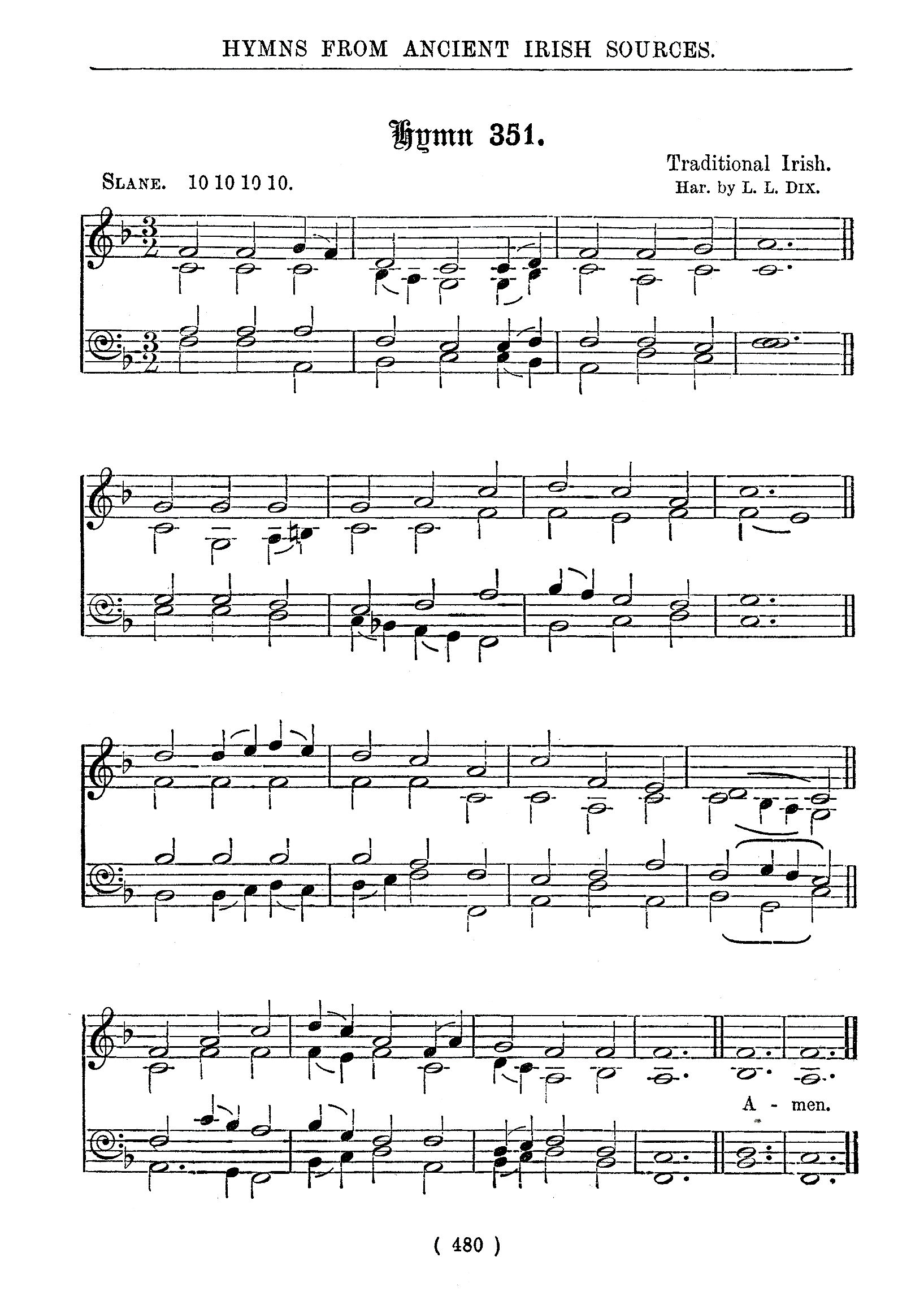

The number “1” sets the default length of notes to be a whole note. The letters are the notes they represent; enclosing them in brackets means to play them simultaneously with the notes not in brackets, and putting them in quotes means to play them as chords. Dashes drop down an octave. If you look at the sheet music (PNG, 170.1 KB) it should all be, if not obvious, decipherable.

I used the script to save each part as a MIDI file and then imported them into GarageBand to assign instruments to them. The instruments used are Fairytales Bells and Granular Vibraphone for the first verse, and Cathedral Organ on both clefs for the second verse. The Amen uses Harp.

I’ve also provided an archive (Zip file, 2.5 MB) of the piano files, if you want to try your hand at using 42 Astounding Scripts’s piano script yourself. The archive also contains the resulting MIDI files, and an MP3 file generated from them.

On the other hand, the St. Michael Hymnal attributes the lyrics as “Irish, c. 700, versified by Mary Elizabeth Byrne… translated by Eleanor H. Hull”. So take that information with a grain of salt. The song is on page 447 of The St. Michael Hymnal. The hymnal also has “Lord of All Hopefulness”, on page 671.

↑

Astounding Scripts

- 42 Astoundingly Useful Scripts and Automations for the Macintosh

- MacOS uses Perl, Python, AppleScript, and Automator and you can write scripts in all of these. Build a talking alarm. Roll dice. Preflight your social media comments. Play music and create ASCII art. Get your retro on and bring your Macintosh into the world of tomorrow with 42 Astoundingly Useful Scripts and Automations for the Macintosh!

- Amen (Slane)

- The Amen tag from the melody Slane, used for Be Thou My Vision and Lord of All Hopefulness.

- Be Thou My Vision piano archive (Zip file, 2.5 MB)

- The archive contains the three text files for the piano script, the three midi files created from them, as well as the mp3 for the music and a copy of the original sheet music.

- Slane (Be Thou My Vision) slideshow, with lyrics: Jerry Stratton at Mimsy@YouTube

- A slideshow of various natural scenes, cathedrals, churches, and aircraft and aircraft carriers under a two-verse melody of Slane.

- Our parental unit, who art, somewhere, maybe

- God’s Blessing Sends Us Forth; We Are the Light of the World; With a Shepherd’s Care. Is there room for God the Father in the modern church? Are the bowdlerizers creating a first-contact crisis?

- Though the Darkness Hide Thee

- Removing mankind from hymns makes them less inclusive and more self-centered. The new language almost always destroys the universality—the catholicity—of the older language. It also has a tendency to deny the necessity of God’s grace.

Be Thou My Vision

- Heart of My Own Heart: Jon Bloom

- “Why I Love ‘Be Thou My Vision’.”

- Slane hymn (PNG, 170.1 KB)

- The arrangement and melody of the tune “slane”, used by both “Lord of All Hopefulness” and “Be Thou My Vision”. From Irish Hymnal with Tunes.

hymnals

- Irish Hymnal with Tunes at Internet Archive

- 1936 Irish Hymnal, from the General Synod of the Church of Ireland.

- The Poem Book of the Gael: Eleanor Hull at Internet Archive

- “Translations from Irish Gaelic Poetry into English Prose and Verse.”

- The St. Michael Hymnal

- “…the hymnal retains the traditional language of the hymns, with no politically driven language. The very few changes in texts are poetic or practical choices. … [it] is still the only Catholic hymnal in this country that includes substantially the entire contents of “Jubilate Deo,” the collection of Gregorian chants that Pope Paul VI sent to all bishops in 1976, asking that they be preserved.”

performances

- Be Thou My Vision - Boyce Worship Collective

- Southern Seminary, Oct 4, 2024.

- Be Thou My Vision - The Petersens (LIVE)

- “We love ‘Be Thou My Vision’ and we learned it for our Patreon community earlier this year after a hard situation. May we never lose sight of what is truly important in this life and where our hope lies.”

- Be Thou My Vision - Traditional (Violin & Harp)

- “Our 2014 New Year Special, an arrangement of the traditional Irish hymn ‘Be Thou My Vision’ to the tune ‘Slane’.”

- Be Thou my Vision by the Bethany Children’s choir

- “Bethany children practising ‘Be thou my Vision O Lord of my Heart’. Video taken July 2022. Bethany is a children’s home for 150+ children and a Primary School for 370+ children in Tanzania.”

- Be Thou My Vision | a new duet version by Abby and Annalie #HearHim

- “Knowing that these words have inspired Christian believers for centuries makes them especially meaningful to our family. Though we have no evidence that our ancestors knew this song, for this video we chose to imagine that they did, and that they sang together while going about their daily activities, as we often do. ”

- Sing My Soul: Lord of All Hopefulness at Internet Archive

- Album of the Washington Cathedral Choir of Men and Boys, directed by Paul Callaway. Possibly recorded for radio, February, 1962.

More Hymns

- Light a candle for Christmas hymns

- While the holidays brought more examples of bowdlerized lyrics they also brought, at least to our church, a lit candle for the darkness, in the form of a new hymnal that retains sound Catholic theology.

- The Soul Felt It’s Worth

- “A thrill of hope, the weary world rejoices…” What is a soul worth? For God, a soul is worth his son.

- Our parental unit, who art, somewhere, maybe

- God’s Blessing Sends Us Forth; We Are the Light of the World; With a Shepherd’s Care. Is there room for God the Father in the modern church? Are the bowdlerizers creating a first-contact crisis?

- Let mortal tongues awake

- Samuel Francis Smith’s America—more commonly known as “My Country, ’Tis of Thee”— is short, direct, and a wonderful hymn to God as the soul of liberty. It’s a perfect hymn for the Fourth of July. It’s also very easy to play using the piano script from 42 Astounding Scripts.

- Though the Darkness Hide Thee

- Removing mankind from hymns makes them less inclusive and more self-centered. The new language almost always destroys the universality—the catholicity—of the older language. It also has a tendency to deny the necessity of God’s grace.

- Five more pages with the topic Hymns, and other related pages

More MIDI

- The Star-Spangled Banner in MIDI

- What could be more appropriate for the fireworks of the Fourth of July than a song about bombs bursting in air, illuminating a great flag rippling defiantly to a hostile world?

- O Little Town of Bethlehem

- How still we see thee lie. Play this song on your Mac’s command line with the piano script.

- I have read a fiery gospel

- “Be swift my soul to answer him, be jubilant my feet.” Written a hundred and fifty-nine years ago today, this rousing abolitionist song remains a fiery call for freedom from tyranny.

- How Great Thou Art

- Then sings my soul…

- Tidings of Comfort and Joy

- One of my favorite Christmas songs. Save us all from Satan’s power, and tidings of comfort and joy.

- Two more pages with the topic MIDI, and other related pages